(Urs Graf 1517

(Urs Graf 1517

Since the whole dress on my woodcut isn’t really visible and doesn’t provide any specific details, I collected woodcuts made by Urs Graf, and sorted them into chronological order to better get an idea of the evolution of a Swiss dress from around 1500 and up to around ten years after the woodcut I based my sleeve on.

The woodcuts aren’t that precise and it’s tricky to figure out if the details just might be left out, or if it’s really part of the construction, though they still gives you some ideas of how to assemble the construction of the dress;

– the neck line is rounded and very low cut both in the front and back.

– some necklines is even so low cut that they goes underneath the bust.

– the shoulders is very far out on, sometimes not even on the shoulders (which also also be a bit exaggerated by the artist since some woodcuts also shows the naked bosom)

– the skirt is very full, but doesn’t have that much of fabric around the waistline, which indicates a triangular cut.

– the skirt seems to be gathered in different ways around the waistline; some is gathered more in the front and back, and others seem to have an evenly distributed gathering around the waistline

– the skirt is usually depicted long with a train, sometimes it’s hoisted up as very common among the woodcuts of German Camfollowers

– it seems more common with just a plain skirt, even though some of them have one or several guards along the bottom part of the skirt

– front opening seem to be common, and some woodcuts even shows a large opening in the front of the skirt.

– slashing around the neckline seems to not be common even though it exists

The Bodice

I favor the four panel construction of my bodice, since it gives more control of the fabric to shape it to fit me properly, and one of the woodcuts from 1514 shows a shade in the back of her that might indicate a backseam. After I finished my bodice, I realize that the low cut back made a backseam a bit unnecessary, and since I have to move the front patterns sides backwards anyways, I will remake the swiss pattern into three pieces for the next dress since it will save me some sewing time.

The construction of the shoulders was a bit challenging; I wanted them to go very far out, but still not fall of my shoulders or hinder my movement. At this point I wished I had more time to finish a proper supportive undergarment that would take off some of the strain from the outer dress, but time is a matter, and I have to wait a little more before I get that done…

When working on the shoulder straps I become a bit suspicious that the woodcuts might be a bit exaggerated; how can you move your arms if you have a dress hanging over them? To be sure that Urs Graf’s woodcuts is actually showing a correct dress, with broad shoulders, I started to look for other Swiss paintings from this period.

Detail of the Meyer Madonna by Holbein (1526-1528)

Holbeins painting of the young daughter of Meyer shows the same type of bodice with the shoulders far apart and with both front and back very low cut. This also shows the that the front isn’t covered by a guard …which I didn’t notice until a little bit to late when I made my own bodice; I didn’t payed enough attention to realize that the Swiss dress looked differently then the 16th c German dresses, and that the guard covering the front opening didn’t showed up in Switzerland until much later …some ad hoc solutions was therefore made on my own bodice because I had to fix my mistakes. Very well, lesson learned…

Since I already had sewn the hooks and eyes on the inside of the dress, I needed a solution to hide the stitches (because I didn’t wanted to remove them all and do it all over again) so I ended up hiding the stitches with a folded piece of fabric around the front edge. Next dress I’m hiding the hooks between the layers instead.

The hooks and eyes are made out of an 18 gauge silver plated bronze wire and attached on the inside with stitches through both layers of fabric.

During the last years I’ve been trying to increase the amount of documentable techniques, tools and supplies. Since I havnt found any sources of using dyed linen thread, (and the dress is supposedly based on a woodcut for a Campfollower, so silk thread isn’t an option), I use a natural linen thread. The thread is therefore hard to hide, so the focus is to just keep it as invisible as possible on the outside, while I let it be shown on the inside.

C. Aneer in her thesis “Skrädderi för kungligt bruk” (Uppsala 2007) have a section about the quality in stitches from a variety of clothes (c 1600-1615) from the a Swedish Royal Armoury, where she reflects over the low quality of the stitches, that the clothes seem to be basically whipped together with no more care then to hold, rather than showing off an elaborate tailoring skills with high quality seams. (Underwear is a different subject; they are incredible neatly stitched together). It might seem plausible consider that outerwear probably isn’t going to be washed in the way as underwear, and therefore doesn’t need the same strong and neat seams as underwear would require.

My thread is therefore visible on the inside and I tried to use just enough stitches to ensure that the dress wouldn’t fall apart …which didn’t really worked since my muscle memory was still set for tiny stitches after the last major project “The Sture Shirt”. I did though use a larger amount of whip stitching then before and the bodice is therefore whip stitched instead of sewn with back stitches.

The fashion fabric is wipstiched from the inside, and then the lining is wipstitched. The picture also show the stitches of the inside of the arm hole, the seam is prick stitched on the outside …and due to lack of economical resources at the moment, I had to use a coloured linen i already had, to line the bodice, instead of buying a natural linen which would have been more historical accurate. That descion was a bit hard to do, but sometimes the mundane life doesn’t cooperate with your perfect ideals.

The guards on the bodice is made by a straight piece, pinned down and steamead to form around the corners in the front and back. By using the light coloured thread, I decided to let the guards fold over and then simply stitch it on the inside. The inside edge isnt folded to keep the layers of wool to a minimum.

Since the sleeves need to be attached by a cord, and i cant find any sources of possible easy-to-use solutions, i decided to simply just add three rings on the inside around the top part of the shoulder, where the corde from the sleeves easy can be slipped into and would not be noticed when i choose to wear the dress sleeveless.

Early 16th c Swiss dresses seems to only have guards around the neckline, the back has a very distinctive round shape and the front seem to dip very low and close to the armholes. The inside of one of the shoulder straps shows one of the rings for the attachable sleeve

Early 16th c Swiss dresses seems to only have guards around the neckline, the back has a very distinctive round shape and the front seem to dip very low and close to the armholes. The inside of one of the shoulder straps shows one of the rings for the attachable sleeve

The skirt

This was the most interesting part because I had the opportunity to try a couple of new techniques! The woodcuts shows that all the skirt has a distinct fall that most probabl can only be achieved with some sort of triangle cut of the fabric (…rather then the rectangular tube construction I use when making German garb). When searching for input of different ways to achieve that look, I study both Mistress Ariana and Mistress Julianas half circular constructions an decided to try one of the Alcega constructions. One of the impressive works that is being done is one mans project of making mini reproductions of the Alcega patterns, and his research helped me quit a long way to easy achieve the look I was aiming for.

If you havn’t seen The Alcega Project yet, please take a moment to look at his blog, it’s a joy to read!

By this point I got a bit carried away and have unfortunately not so many picture of the process; but you can se my transfer of the original pattern on to my double folded fabric (which gives you a straight grain in the front and back) and the little interesting detail of the different sized triangles whichs helps flare out the skirt in the bottom. (The small picture shows the different in length of back and front, which I decided to keep to give the skirt a little bit of a train)

The pattern gives you two non symmetrical triangular shapes on the side of the dress

The hem

The wool I use is light weight, so I took the opportunity to try a technique a talented friend of mine used for her latest 16th German dress (Adelheit is one of my favorite choice to discuss 16th century sewing with, I warmly recommend to visit her newly started blog) which gives a bit extra stability …and also protects the hem and makes it look a little bit like I actually have an underskirt (California, you’re a very hot lady). Different ways to add extra stability and sturdiness can be seen in extant pieces, and with the information provided by Adelheit from her tries, I gave it a try;

1) The brown fabric is back stitched to the edge, then folded over a piece of double folded left over heavy weight wool fabric I happen to have in my scrap stash. Small running stitches keeps the inner layer of wool in place.

2) The orange fabric is then prickstitched on the front side to keep it flat and adding some extra weight

3) The brown fabric is then folded and stitched, which can be seen some from the outside

4) I experimented with different kind of stitches; as a Campfollower, I probably wear the skirt hoisted, which would make the seam of the hem visible. I tried both wipstitch and running stitch but instead used a hidden running stitch (to the left) which is basically hiding the thread inside the fabric

The width of the brown fabric is simply decided by the fact that I use a light weight wool which makes the final stitches very visible, so I went for just about 1 1/2″, enough to give stability, but not too wide so I kept the front side stitches close to the hem.

The Skirt Guard

There isn’t that many 16th c Swiss dresses with a decorative guard on the skirt, but since the dress is planned to be worn with out the fancy sleeves, I wanted to add something extra to cheer it up a bit …and also challenge myself to try to add a straight piece of fabric to a curved skirt.

The original woodcut doesn’t show the full figure, which gave me some freedom to design the rest of the look on the dress, and I decided to use this guard design because it gave me the opportunity to add both brown and an additional yellow colour.

The original woodcut doesn’t show the full figure, which gave me some freedom to design the rest of the look on the dress, and I decided to use this guard design because it gave me the opportunity to add both brown and an additional yellow colour.

The reason I choose to finish the hem before adding the guard was to make sure I had an even edge to work from when marking out the path of the guard (my Smocking ruler was very handy to use).

The reason I choose to finish the hem before adding the guard was to make sure I had an even edge to work from when marking out the path of the guard (my Smocking ruler was very handy to use).

The top part is pinned and stitched first, since it’s the shortest length due to the cut of the skirt …the bottom part need some stretching before its pinned, and I wanted to be sure that the top wasn’t going to move. The yellow wool is simply double folded and slipped in between the lathe here, saving me some sewing time.

The bottom part is then steamed and pinned in order to follow the curve of the skirt

Before picture of the guard before its steamed and ironed flat. The construction of the skirt with the straight front and the flares on the sides, actually made this step easier then anticipated; I basically just need to start in the front and back and pin the guard against the sides until it started to crinkle, and then I steamed the fabric between this two points to form the guards to follow the curve of the skirt.

The yellow fabric is slipped in before I start to sew;

When you don’t want to pin all layers together (or pin on the ironing board as I did here since I was still using the iron to flatten the guards) you can always put something hard underneath to prevent the pin to go through to many layers (I used my ruler for example)

…then all its left is to attach the skirt to the bodice, in this case I used evenly rolled pleats (woodcut number 3), attach the inner lining to the skirt and attach the sleeves and take a picture of the dress hangin on my dress form, until I can use it for the next event!

Woodcut 1 and 4 is the same woodcut, and shows the inspiration for the neckline and the guards.

Woodcut number 2 is the original I used as a base for this dress project with the fancy sleeves

Woodcut number 3 shows the inspiration of the pleating technique I used.

Update: I havn’t still got the time to take a clear picture, but some of my friends have at least managed to catch me in different angles during this past weeks;

Pictures taken by B. Rudmann

The pattern based on the two above woodcuts; Front and back (note that the back mid seam is against a folded edge), the measuments are calculated for an XL Male.

The pattern based on the two above woodcuts; Front and back (note that the back mid seam is against a folded edge), the measuments are calculated for an XL Male.

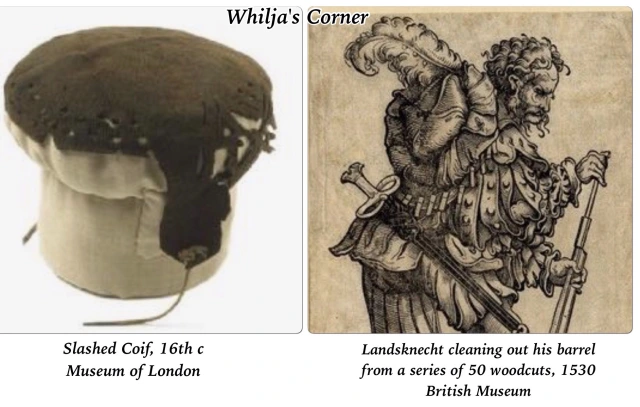

left: photos from J. Arnold Patterns of Fashion 4

left: photos from J. Arnold Patterns of Fashion 4